Last modified 22 July 2006 19:00 Eastern Time

The ruins of Urquhart Castle is a fun place to explore. Located on the shores of Loch Ness, it’s an exploded and decayed ruin which has recently been stabilized by The National Trust for Scotland.

Until a few years ago, I understand it was undisturbed and therefore a rather difficult place to explore, as well as perhaps somewhat dangerous. Anyone in a wheelchair need not bother coming by, as it was a steep climb down an embankment to get to the site. That’s all different now, and the free exploration has been vanquished for your convenience at the cost of lots of touristy trinkets and an admission charge.

On the other side of the equation, they added a nice visitor’s center with handicapped access and a theater featuring a quick history lesson to explain the significance of the ruin. You lose some, you gain some.

Anyway, the picture at the top of the page is an overview of the site from the parking lot. You can’t see the visitor’s center from there, as it’s buried under the lower parking lot. I do not mean to imply the Trust did a poor job here! Not at all. They’ve made the ruin much more accessible. The other side of that is that it’s less “real” than it was. Also, it’s now equipped with little signs explaining the different parts of the castle and what they were when you see them.

Also, the tower has clearly had some structural reinforcement.

After I passed through the visitor’s center, I walked through a patio and went down a ramp toward the trebuchet.

|

The TrebuchetThe trebuchet is a catapult, much used in siege warfare before the development of gunpowder. There are references to them in the literature of China, medieval Europe and in almost contemporaneous Arab literature. One of those involved with the building of this machine had for reference a copy of one such Arab manuscript. A large trebuchet (the machine before you is only middle-sized) could throw missiles weighing more than 100kg more than 500 metres and with sufficient accuracy to be formidable and effective against fortified positions. This trebuchet can throw a stone ball, like those weighing some 113kg (250 lbs) that you see lying in front of the base, a distance of 180 metres. In so doing, it seriously damaged a purpose-built target wall that stood just over the brow of the hill to the south, where construction work is now taking place. Power for the throw is generated by the falling counterweight attached to the lower end of the throwing-arm that in this example weighs about 7,000kg. The frame including the axles and wheels are built of green oak. The throwing arm is a Douglas Fir tree trunk some 8.8 metres (29 feet) long cut from the forest on the opposite shore of Loch Ness. Larger trebuchets were also fitted with buckets (rather than having fixed weights), pivoted to the lower end of the arm, into which any suitable and heavy material could be placed to provide the power. This refinement, originating in France, simplified adjustments (in that massive and unwieldy counterweights did not need to be made) since the range was adjusted by filling or emptying the bucket to vary the power. The throwing arm is cocked by suitably rigged ropes and held by a trigger mechanism. Cocking a trebuchet using ropes to draw down the arm required a great deal of manpower, and winches were often used to ease the task. The direction of the throw can be adjusted either by swinging the whole trebuchet on its base - not an easy task at any time - or, within narrow limits, by angling the missile slide resting on top of the base. The missile in its net sling rests on the slide prior to the throw. On releasing the throwing arm, both are dragged along the slide until hoisted in the air. The moment when the sling is released, freeing the missile to do its work, is determined by the shape of the hook at the top of the throwing arm. Get this wrong and the missile will fly anywhere except sideways or to the target. Getting the missile’s trajectory just right was time-consuming; much trial and error would have characterised the effort. However, once set up and ranged-in trebuchets were very destructive. The only reliable defence against them was to prevent their construction in the first place. History records that trebuchets were used to throw almost any and every kind of missile that was to hand. Dead animals (especially if diseased) and Greek Fire (burning tarballs) were among the more obnoxious objects used to demoralise and weaken the besieged. A detailed account of trebuchets in general and of the construction of this trebuchet, and its larger sister now on show at Caerlaverock Castle in the south of Scotland, appeared in the January 2000 issue of The Smithsonian. Assisted by carpenters from this country, both trebuchets were built from raw timber by timber-framers from the US, for the making of one of a series of television films entitled Secrets of Lost Empires by the Boston-based company WBGH/Nova. From delivery of raw timber to firing the missiles took three weeks in October/November 1998. The resulting film - Medieval Siege - is to be broadcast in the UK on Channel 4 TV at 9pm on 1 June 2000. It is recommended viewing - check the transmission time and do watch it (and the four to follow that deal with other related topics)! |

I then made my way toward the ruin, over the nice bridge on the paved path through the well manicured lawn. You can see how they’ve paved the paths and added safety railings to the walls and tower. Or maybe the picture is too small. Oh well, I don’t have infinite hosting space at this time.

Here’s a view of the trebuchet again, on the shore of Loch Ness.

| Welcome to mighty Urquhart Castle, Loch Ness You are following in some famous footsteps. |

|||

|

|

|

|

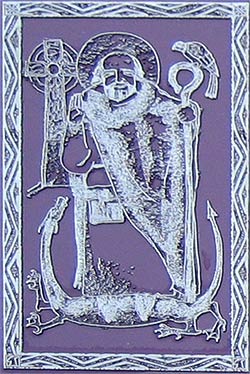

| St Columba of Iona ~ AD 580 |

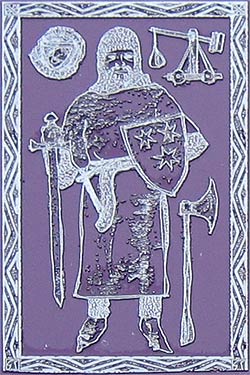

Sir Andrew de Moray ~ AD 1297 |

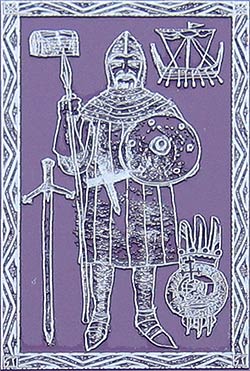

Sir Donald MacDonald, Lord of the Isles ~ AD 1395 |

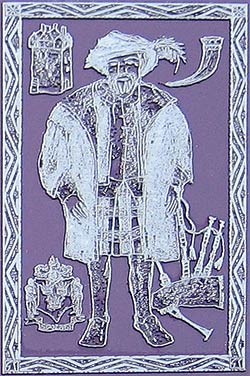

Sir John Grant, Chief of Clan Grant ~ AD 1509 |

Columba stopped here to baptise a Pictish nobleman called Emchath. His residence was originally situated on the rocky summit to your right. A fine Pictish brooch was found at the castle; a replica is on display in the visitor centre. |

Sir Andrew attempted, unsuccessfully, to retake the castle from English possession. The great ditch in front of you and parts of the defensive wall survive from that time A silver coin of Edward I of England found at the castle is on display in the visitor centre. |

The powerful Lords of the Isles made life a misery for the people in Glen Urquhart from the time they first appeared in 1395. Many of the objects in the visitor centre date from the MacDonalds’ occupation, including the bronze water jug — the Urquhart Ewer. |

Sir John found the castle in a sorry state when he became the owner on the downfall of the Lords of the Isles. He began rebuilding anew. Much of what you see today was built by him, including the lofty Grant Tower to your left, from where you get great views of Loch Ness. |

| Before you leave the castle, make sure you don’t miss the marvellous array of objects found here at the castle and now on show in the visitor centre. | |||

Here’s the bridge and main entry way.

|

Here’s a really great image of Grant Tower, if I do say so myself. |

| Here’s the other side of Grant Tower, where you can see what they did to it. I suppose it’s safer now. Certainly, the added flooring is easier to handle than empty air! |  |

A steel spiral staircase, added recently. I rather like this image.

We had almost enough time at Urquhart Castle. I got many more pictures there, but these are the best of them. I think I got pics of just about everything. That’s not to say they’re all worth seeing.

Next up, we went to Fort William.