Last modified 18 June 2007 22:01 ET

We came to the Distillery on a narrow road with approximately just enough width for our motor coach as far as I could tell, and came upon a place with lots of buildings.

The bigger building in the back of the above image is the distillery itself. I’m not sure what the other buildings in the picture are, excepting the one hidden behind the bush on the far right, which is where tours start. See it again on the left, below:

|

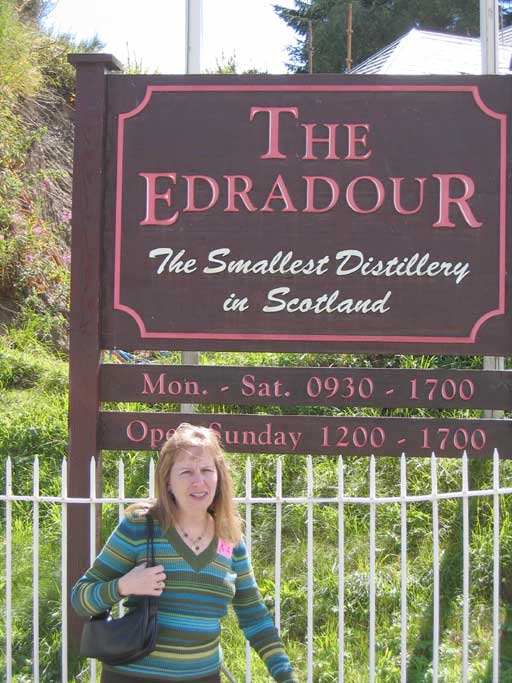

Here’s another view of the sign, which should be easier to read. That’s Val Ontell, one of the package trip organizers, in front of the sign. |

Next, we went inside the building I’ve been talking about, the starting point. It’s an introduction to the Distillery. In the center is the display case to the right. |

|

Instead of including the images of the text displays, I think I’ll just include what they’re saying. After all, this ’page is already graphics-intensive. Note: if Edradour has a copyright problem with this page, please contact me so we can arrange something appropriate.

|

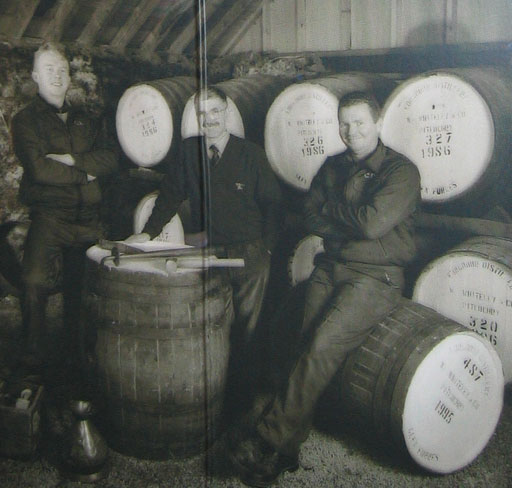

The Staff of EdradourPaul Paterson and Sean Campbell, the production staff who handcraft The Edradour, guided by John Reid, Distillery manager. |

Scotch WhiskyDating back to 1216, it’s small wonder that the Clan Campbell has made such an impression on the moulding of Scottish history. The Campbells, or Argyll Militia as they became known, played a leading role in the defeat of the Jacobites. In the fierce battle of Culloden the Campbells fought at the front line. Captain Colin Campbell also led the Black Watch in the same battle, losing his life in the onslaught. In keeping with the great heritage of the Clan Campbell the distillery has carefully selected only whiskies of the highest quality to produce a blend worthy of the noble name of Campbell. |

|

Duke of Argyll and Clan CampbellThe present chief of the Campbell Clan, the 12th Duke of Argyll, lives in Inveraray Castle. Fluent in six languages, the Duke maintains an avid interest in traditional distilling as a Directory of Campbell Distillers Ltd which owns Edradour Distillery. The Campbell Clan, with records dating back to the 13th century, is one of the most prominent of all Scottish clans. Its story interweaves and spans the country’s history from 1306 when Sir Neil Campbell fought alongside Robert the Bruce to 1906 when Sir Hentry Campbell-Bannerman was elected Prime Minister of Britain. The Clan Campbell whiskies, previously exclusive to the Dukes of Argyll and the senior members of the clan are now commercialised and are enjoyed by whisky lovers around the world. The Clan Campbell and Clan Campbell Highlander whiskies contain Edradour as an integral part of the blend. But only the master blender knows the ancient recipe. |

|

House of Lords and William WhiteleyWilliam Whiteley, born 1856 was a distiller with a formidable knowledge of whisky and a quest for perfection in whisky blending. To prevent his sense of smell being compromised by pollutants such as smoke he never travelled by train and to keep his palate sharp he drank plenty of spring water. Whiteley was constantly striving to create flawless premium whiskies, regardless of the time and cost involved and he felt that Edradour was a vital ingredient in achieving these. Therefore, in 1925 he purchased the distillery, enabling him to have sole access to this exceptional malt. Every drop was commandeered for his development projects. House of Lords whisky was the result of his work. Orders for the outstanding product arrived daily at Edradour from Royal households, transatlantic luxury liners and elegant hotels such as the Savoy. |

|

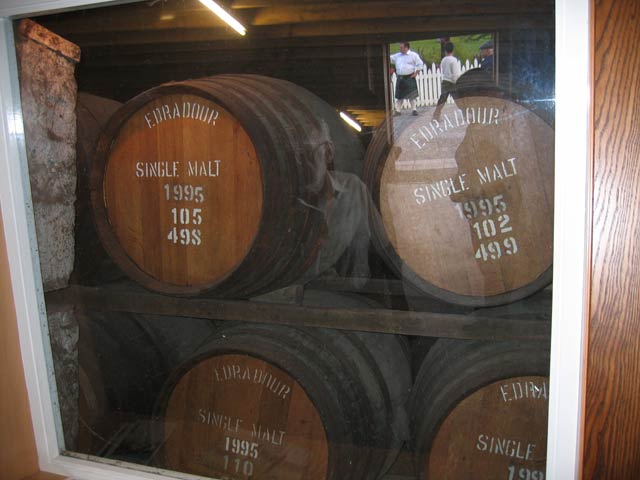

10 Years MaturationMaturation is the mellowing of whisky, as it is stored in oak casks. By law the spirit must be matured for 3 years, before it becomes “whisky”, though here at Edradour it remains in oak casks for at least 10 years. In the first year about 4% is lost through evaporation and this amount falls to around 2% in subsequent years. The distillers’ charming expression for this is “the angel’s share”. Various types of cask can be used for maturation. At Edradour we prefer to use only oak casks which have contained sherry, since these help provide the unique flavour, colour and bouquet of Edradour. |

|

Speaking of casks, here are some behind a window:  |

|

History of EdradourWithin two years of the 1823 Excise Act a group of local farmers — the founding fathers of Edradour — decided to set up a co-operative distillery, in these very same buildings in which you are now standing. The distillery changed hands several times during the 19th Century. Ownership passed from William McIntosh, one of the original farmers, to his son John who was later succeeded by his nephew Peter, the son of an exciseman. There is an unsubstantiated story that the distillery was at one time owned by the Mafia. What is more certain is that in 1924 William Whiteley bought the distillery. Finally Edradour was acquired by Campbell Distillers Ltd in 1982. Today, with little more than a lick of paint and whitewash, life at Edradour goes on with the same equipment and ancient distilling methods. With a staff of three, and an annual production equivalent to the amount produced by a typical Speyside distillery in a week, Edradour remains the smallest distillery in Scotland. |

|

Collecting the TaxesAfter the Union of Scotland and England in 1707, the new Parliament established a board of excise to enforce the tax. This outraged the Scottish farmers and protests in Edinburgh and Glasgow turned into full-scale rioting. Soon it became apparent that collecting the taxes was not as straightforward as the Union had imagined. Commissioned by George 1, General Wade, Commander of the forces in Northern Britain, drove military roads through the Highland mountains. Whilst this opened up the highlands it did little in helping excisemen collect taxes. By the 1820s successful raids on illicit stills mounted to 14,000 in a single year. Considering they were fighting a losing battle this highlights the great extent of illicit distilling. Parliament began to realise that a more viable way to curb the black market would be to make legal distilling more attractive. So in 1823, the Excise Act was passed which reduced the minimum legal still size from 500 to 40 gallons. (A licence to manufacture whisky cost £10, with a tax of 2s. 3d. on each gallon.) Within 10 years seizures of illicit stills had fallen to 692 a year. |

|

The (missing! “History"?) of the SpiritIt is generally believed that the art of distillation originated in the Far East. When it first reached Scotland is uncertain, but it has been suggested that St Patrick introduced distilling to the Scots as early as the 5th Century. The production of Scotch whisky using malted barley started later, possibly around the 11th or 12th century, although the first known record is in the Exchequer Rolls dated 1494. Distilling in Scotland was a natural by product of farming life. The three key elements needed to make fine malt whisky were readily available. Barley, which was harvested and stored to feed the sheep and cattle through the hard winter. Peat, lay deep and abundant and was used to fuel the hearth and provide heat for cooking. Ice cold water flowed freely over the rocks. Inevitably, as the popularity of whisky distillation grew the government saw it as a source of revenue. In 1644 the Scots parliament imposed a devastating levy, or malt tax, of 2s. 8d. on a pint of “strong liquor”. (In those days a Scots pint was approximately one third of a gallon.) This forced what was a thriving cottage industry to take to the hills to continue distilling, out of sight of the exciseman. |

|

RegionsJust as the wines of France are grouped by region, so are the single malts of Scotland. These are the Highlands, Campbeltown, Lowlands and Islay. The Highland malts, from by far the largest of the regions, have the widest variety of characteristics. In the west they have a rounded, dry character with some peatiness. The far north tends to produce whiskies that are heathery and spicy. Speyside produces a highly refined smokiness. Whiskies from the more southern highlands also have a fruity hint. Edradour is acclaimed as the jewel in the crown of Highland malts. The Lowland whiskies are altogether more calm and low profile, with a soft sweetness. Islay, lashed by wind, rain and sea produces malts noted for their seaweedy character. Campbeltown is the smallest of the whisky regions. Though very important at the beginning of the century only two distilleries now remain producing malts with the distinctive briny flavour. These regional variations provide guidelines as opposed to rules. There are few standard descriptions of whisky. But what remains common to all is that the art of making scotch whisky, perfected in the 19th century, is unrivalled by pale imitations around the world. |

|

The Scottish ClimateIt’s widely appreciated that the warmer countries grow fruits, especially grapes, which can be used to ferment wines and brandies. Fewer of us have made the connection that cooler nations cultivate grains instead, which can be used to produce beers and whisky. Being a cool, damp country, Scotland is the perfect location for distilling. Just as the chateau-bottled wines from the same family of grape vary enormously according to the water, sun and soil, so do the single malts. The water used to make the whisky is of utmost importance to the ultimate taste. The water may flow over granite and peat and pick up some flavour from this. At Edradour the water is slightly peaty and you may taste this when you sample our single malt. The limited quantity and exceptional quality of Edradour can be compared to Chateau Petrus, the superios Bordeaux wine which is fermented in very small quantities. |

|

Single Malt Scotch Whisky The water of lifeA single malt scotch whisky must fulfil three criteria;–

There are about one hundred malt distilleries in Scotland. In addition there are a small number of distilleries producing grain whiskies, which use other cereals and a different method of distillation. |

|

|

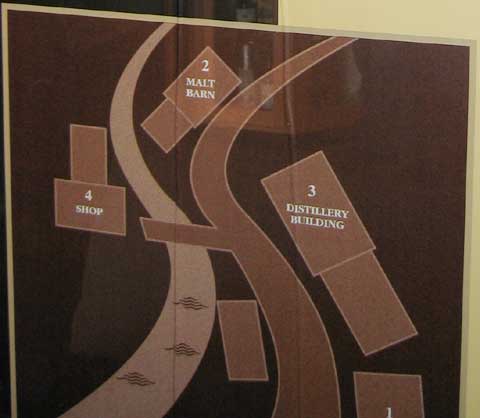

Edradour DistilleryEdradour as you see it today is virtually unchanged in over 150 years. The Reception (1) where you are now was originally where the whisky casks were stored. The Malt Barn (2) where the barley used to be malted is now our tasting room. Production still takes place today in the original Distillery building (3). The methods used are also unchanged in 150 years. During the days of illicit distilling the “draft” (what was left at the end of the process) was fed to local cattle, often without the farmer’s knowledge, to hide the tell-tale sign of an illicit still nearby. The Shop (4) was originally the Distillery Manager’s Home. Note that the bottom of the map was cut off in the original image. (1) is in the lower right. |

|

Our guide came, introduced himself (sorry, I don’t recall his name), and led us to another large building, which was described on the map above, as the Malt Barn. Wish I had a better picture of you man, but this is the best I’ve got. |

|

We left the distilling building, walked across the way, and into their on-site store. Gee, they sure have a lot of their whisky here, and some from associated distilleries too.

By the way, when I was asked by one of the people in the store if I liked the sample, I should have been more clear. I stated flatly that I didn’t. What neglected to say, which should have been said, was that that taste was my very first taste of any kind of whisky (or whiskey, for that matter). I’ve never been a drinker, and I’ve found that I like scotch. I’m working on educating my palate as I can! And regular Edradour is available locally to me... so please accept my apologies, guys. I’ve bought some regular Edradour even though I’ve yet to finish the Rosebank I bought on-site. And I must say I think it beats the heck out of the Rosebank. Having also picked up a bottle of Oban, I think I’ve come to understand why they closed the Rosebank distillery. Ah, well.